I was not as close to my aunt as I should have been. I did not know how she felt about her life or the world or what her favorite bird was. I have no idea, for example, if she ever watched Bugs Bunny dressed as Brünnhilde while singing opera or if she found it as strangely arousing as I did. Her thoughts on macaroni and cheese, ghosts, and aliens remain a mystery. She rarely spoke, but when she did, she was dry, exacting, sarcastic. As one woman confided in me at her funeral this morning, “She didn’t say much, but I knew I didn’t want to cross her.”

But my aunt also baked cookies for everyone in the family at Christmas–gingerbread, chocolate chip, and snickerdoodle, all packed tightly together in the same tin so that everything became faintly spiced. A few months ago, she sent me a handwritten recipe card for her sour cream chocolate chip cookies, as if she knew she would not be able to make them this year, and the stern instruction: mini chocolate chips only.

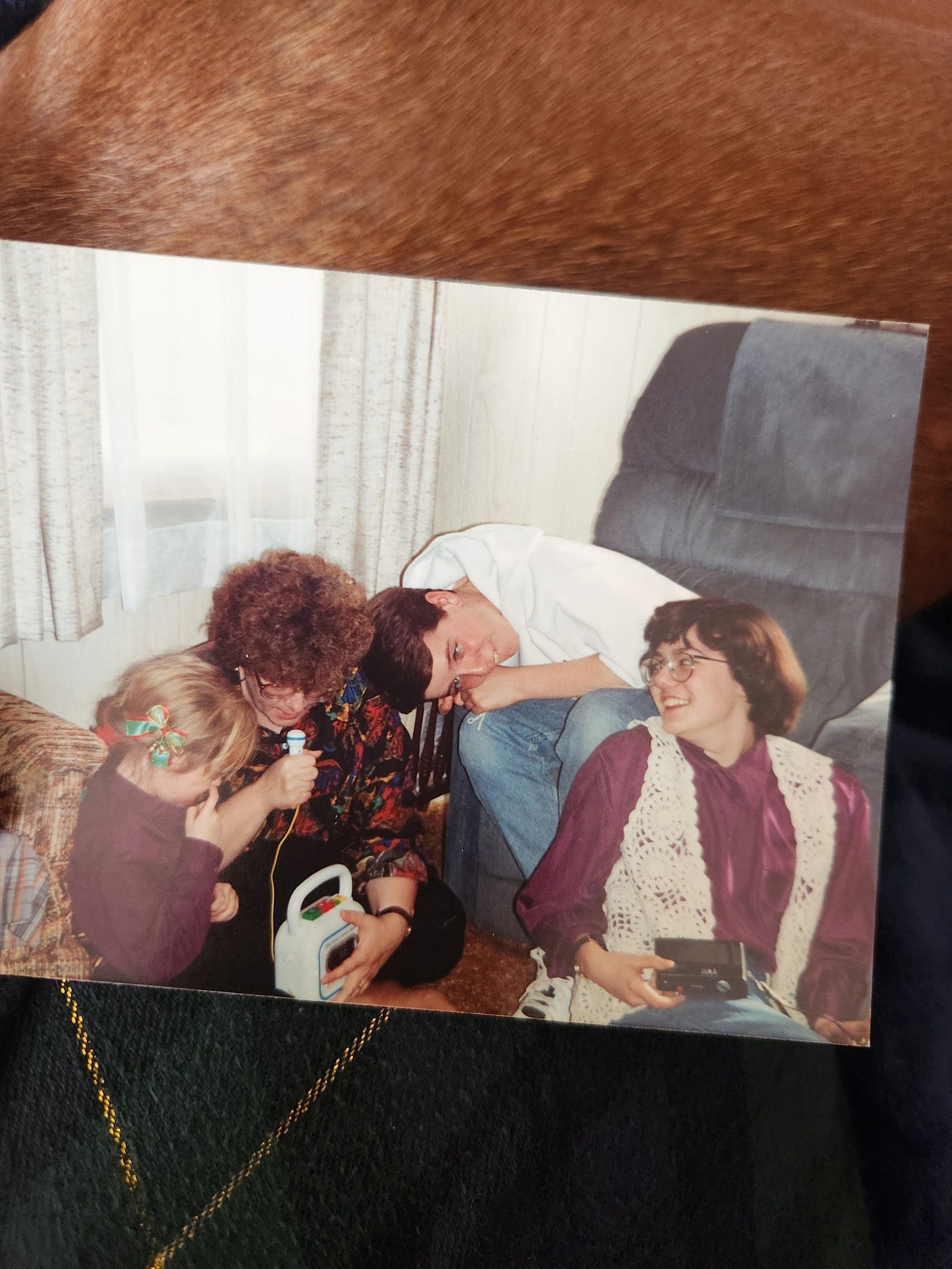

Her hobbies were cross-stitching and making handmade cards which she mailed for every family member and friend's birthday, including that of her post office carrier. We found only one cross-stitch that she kept for herself; the rest she gave away. My aunt liked to sit in the corner of the room during a holiday celebration, smirking and snapping photos. At the end of each family gathering, she would ask my mother to herd us into various formations while she clicked away.

We never saw the photos until after she was gone, piled boxes and albums depicting a lifetime that began in 1947. Much of my time the last few days has been spent in my aunt’s apartment who died a week ago after a brief confrontation with stage four liver cancer. She lived alone in a senior facility and wanted my sister and me to be the first to go through her things. As I looked through her carefully labeled and organized record, I saw my family through her eyes.

She snapped so much more than those end-of-the-party images of all of us standing sweetly together, smiling in our Christmas sweaters or Easter dresses. Any time someone was making a funny face or doing something silly, she captured it, often without them realizing. In this way, I learned the geography of her love.

Recently, Berkeley philosopher Alva Nöe posed a controversial idea in his Presidential Lecture at Stanford: What if love is the thing that creates consciousness?

“We don’t love because the ones we love are so impressive or so charming or so beautiful or good. There isn’t really any fully formed person there for you prior to the unfolding of your relationship with them…You enact them in the work of coming to know them. Love is the commitment to this work.”

Because I believe Mary Oliver who said in her essay collection Upstream that “attention is the beginning of devotion” and Simone Weil who argued that “attention is bound up with desire,” I see attention and love as synonyms. (Weil also happened to mention in Gravity & Grace that “among human beings, only the existence of those we love is fully recognized” and “the poet produces something beautiful by affixing his attention on something real. It is the same with the act of love.”)

Nöe's lecture had me wondering if our attention (and, therefore, our love) is the very thing that creates us, if–like quantum particles–we must be looked at to become.

[If so, then Hannah Arendt was right when she identified loneliness as the core disease of humanity and the origin of totalitarianism, and it confirms hatred as a baser form of consciousness. It also aligns with what we know about the fluidity and contextualization of personalities. But those are thoughts for another day.]

I’d like to tell Weil that the week my aunt died, I began to wonder if paying attention creates consciousness–both in ourselves and in others. I imagine she would tell me that each time we notice, our worlds become more complex, our fractals extend, and our understanding of the nuances of both self and connection increases. Although it is more likely that Weil would tell me to put this laptop away and put my hands to some real work.

Mathematically, logically, philosophically, love as a generator of consciousness is not that outlandish of an assertion and, frankly, one that is only really novel to Western audiences. Every action creates the opportunity for more action. Each step forward generates an infinite number of possible second steps. The beauty of life is that which is found in community. When we notice, we create synapses that hinge us to one another and invite more.

Tonight, as I began to unpack items that will now forever make me think of my aunt—carefully folded handkerchiefs and a hummingbird brooch—attention came to mind again, this time in the way children are so eager to show off their rooms and toys, as though desperately seeking the affirmation of their existences through our nodding praise of their action figurines. Children know better than we do that attention elbows out the space for the expansion of life, that noticing is knowing. We must be observed in order to be.

Attention is desire. Attention is love. One’s first memory is the first moment of noticing, one’s personal Big Bang, the ceremonial breaking of John Locke’s tabula rasa, the spiritual conception of awareness. I wonder whether my noticing of my aunt now, the regard I can offer as I look at a glass candle holder or a toaster, might still contribute to the persistence of her consciousness. Will holding her photos in my hands continue to create her life?

I met many women over the years who knew my aunt–those who lived beside her in her apartment building and those who worked with her at the shoe factory where she was employed from seventeen to sixty-two. In the weeks leading up to my aunt’s death, I ran into her friends who offered me Polish sausages and sauerkraut to take with me to the hospital and who congratulated me on my “many accomplishments.” I didn’t know any of their names, but the people in my aunt’s worlds recognized me immediately. I realized later that this was because the photos my aunt had taken weren’t for us. They were to show her friends.

The face she made when I asked her if she wanted sausages and sauerkraut was her final wry joke.

My aunt constructed my consciousness, manifested me from mere molecules of air as she showed pictures of my siblings and me to her neighbors. She expanded our existences while watching us quietly from the corner. Like Nöe, she understood that, in order to love and be, “the first step is just paying them enough respect to notice what is actually in front of you, and not take for granted the fact that they are there.”